High Bar Squat Vs. Low Bar Squat

Why I don't do the low bar squat.

High bar squat or low bar squat, which is better? That is the question many strength trainees ask and here I will explain why I favor the high bar squat.

I became interested in this question once I resumed training barbell squats in October 2017 after years unable/unwilling to do them due to injuries. As the title indicates, after doing some research, thought and experimentation with the two types of squatting, I have decided that the high bar squat has advantages for strength training and bodybuilding. Although I generally like Mark Rippetoe's Starting Strength book and program, I think the high bar squat is a better choice for strength training and bodybuilding than the low bar squat that he recommends, for reasons given below.

Before diving in, let me emphasize that squatting for strength training may differ from squatting in order to lift as much weight as possible for competition. I argue that for building strength in the thighs and hips, the high bar squat is preferable to the low bar squat. However, for lifting as much weight as possible to win a powerlifting competition, the low bar squat might be best, at least for some people.

Why do we squat? To build full range strength and muscle size in the hips and thighs, particularly the front thighs, consisting of the quadriceps femoris. So, which builds greater full range strength in the hips and quadriceps, the high bar or low bar squat?

High Bar Squat Builds Full Range Strength

Olympic lifters have chosen the full high bar squat as their preferred squatting method for decades.

What constitutes a full squat? Sometimes called an “ass-to-grass” (ATG) squat, a full squat involves going through the full range of motion available when squatting.

It means going down as far as you can go, limited only by the anatomy of your body.

A full range of motion for the knee means that the knee goes from fully extended or open – the thigh and leg at an angle of 0º – then closes completely, with the back of the thigh in full contact with the back of the lower leg, at which point the outside angle between the thigh and the lower leg approximates 135º (inside angle of ~65º).

In his article King Squat, Marty Gallagher, the author of The Purposeful Primitive who has competed in both Olympic lifting and power lifting, wrote:

Marty aptly compares half or parallel squats to bench presses. In a proper bench press we lower the bar as far as possible, to the chest. We do not do half bench presses limiting elbow angle to 90º or “parallel bench presses” lowering the bar only until the upper arm is parallel to the floor. Nor do we lower the bar only to the point where the elbow is just below the shoulder joint. These all count as partial ranges of motion in the bench press. Like a partial squat, a partial bench press allows one to use a greater load, but it does not provide a better training effect. Unless anatomically limited, when doing the bench press you lower the bar until it touches the chest, which generally marks the full ranges of motion at both the shoulder and the elbow.

|

"Imagine if a man is bench-pressing and this man has a full range-of-motion, a chest to lockout rep stroke of 18 inches. He begins doing "half" bench presses, stopping the barbell halfway down, lowering the barbell (or dumbbells) 9 out of 18 inches. By shortening the rep stroke, the bench presser is suddenly able to handle a lot more poundage. Over time, his ego causes him to shorten this already shortened rep stroke further. Now, instead of lowering halfway down he lowers the barbell a mere six inches before reversing directions and without pause push the payload upward. "He can now handle a huge amount of weight - and he practices his 6-inch rep stroke bench technique exclusively for the next few years. He becomes capable of handling 315 for 8 reps in the six-inch bench press - but his dirty little secret is if he accidentally goes one inch below his six inch ingrained power stroke, he has no strength, none, and the barbell will collapse on him like a building in an earthquake. "Because our six-inch rep-stroke bench presser has never trained outside his particular zone of strength, if he were to experience a lapse in concentration and without thinking lower 315 eight inches, his arms would collapse and the 315 would crash down on his chest, delivering all its fearful concentrated impact in the form a 1¾ inch round barbell. That's a surefire rib-breaker. Plus, from a muscle and strength building perspective, partial reps yield partial results. "We have the identical situation in squatting. We somehow have been talked into the weird equivalent of not lowering the bench press bar all the way down to the chest: why wouldn't we squat all the way down? Why do we purposefully curtail the rep stroke length, and thereby the results - by only descending to parallel - or higher. Those few that bother to squat in our Virtual Age will do half squats, the exact equivalent of the guy that only lowers the bench pressing bar six inches. At least the parallel squatter goes halfway down. While we have no problem grasping the ridiculousness of the half-bench or the six-inch bench press, the ludicrousness of the half or parallel squat eludes us." Marty Gallagher, King Squat |

Due to genetically determined anatomical factors – namely, long femur bones accompanied by short torso – some people will not be able to do barbell-loaded ATG squats with a neutral lumbar spine. Nevertheless, biomechanics predicts that even these people can achieve a deeper barbell squat, with a greater knee and quadriceps ROM, while still maintaining a neutral lumbar spine, when using a high bar placement rather than a low bar placement.

The low bar squat makes it difficult or impossible to achieve a deep squat or full range of motion around the knee, because he low bar position reduces the length of the lever formed by the spine. In order to keep the bar over the mid-foot where it belongs, you must lean forward more than in the high bar squat. This generally causes the hip joint to close fully before one reaches full closure of the knee joint. People who have long femurs and short torsos may not even be able to reach a parallel squat position with a neutral spine if they use a low bar placement.

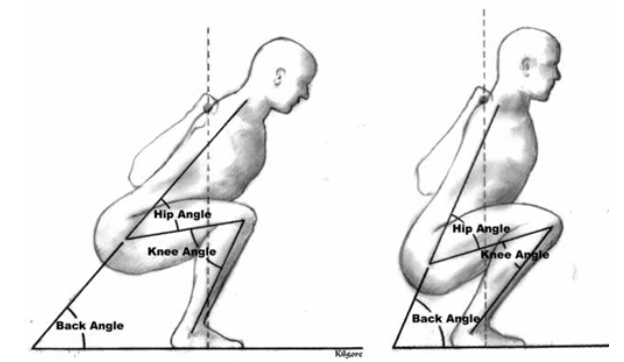

In other words, as illustrated below, in the low bar squat, the forward

lean results in the torso contacting the thighs before the thighs

contact the calves. This may explain why advocates of the low bar

squat prescribe squatting down only to the point where the hip crease

is below the knee. Most people will not be able to go lower with a low bar squat.

Left, low bar squat; right, high bar squat. Note the lower hip position, more closed knee, and almost parallel lines of the back and leg for the high bar squat. Both hip and knee have reached the limit range of motion in the deep position of the high bar squat but only the hip is fully closed in the deep position of the low bar squat. Image source: <https://steemit.com/fitness/@orupold-fitness/high-bar-vs-low-bar> FAIR USE

Some authors suggest that the low bar squat places more load on the hamstrings and glutes than the high bar squat. Contreras et al compared the hamstring and glute activation in parallel, full, and front squats.1 The front squat and parallel squat differed markedly in forward lean, the difference much greater than between the high bar and low bar squat. Despite this, they found no significant difference in gluteus maximus or hamstring activation between the three variations; however, the full and front squats produced greater quadricep activation than parallel squats despite being performed with lighter loads.

Bryanton et al. found that increasing squat depth increases the relative muscular exertion (RME) of the quadriceps and both greater squat depth and barbell load increases the RME of the hip extensors.2 Thus, even if the low bar squat did increase the relative load on the hip extensors, it tends to reduce the load on the quadriceps, whereas going deep with a high bar squat appears to increase the training load on both the quadriceps and the hips.

In summary, biomechanical analysis and supporting research indicates that the low bar squat produces no greater training effect for the hips and hamstrings than the full high bar squat, but using a low bar position probably produces a lesser stimulus for the quadriceps. Therefore, barring anatomical restrictions preventing it, the high bar squat is likely the superior choice because it definitely provides a similar if not greater load to the hip extensors, and provides the greater load for the quadriceps.

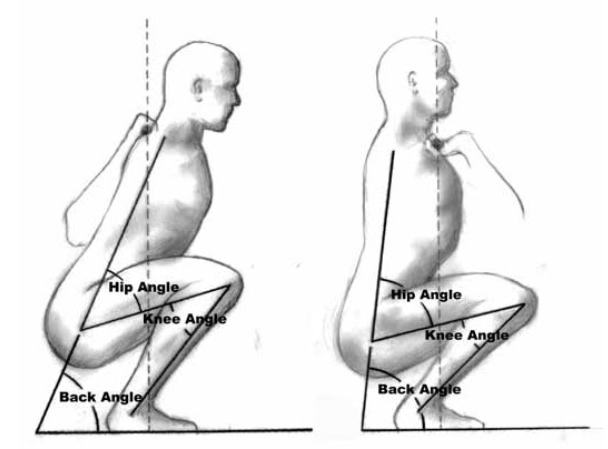

Left, high bar squat; right, front squat. Note that in the high bar squat, the back and leg are almost parallel in the bottom position. Image source: <http://www.healthfreedoms.org/health-benefits-of-the-natural-squatting-position/> FAIR USE.

Squats Don’t Train Hamstrings Anyway

The hamstrings can’t contribute significant force to any squat variation

because they cross both the hip and knee joints. As one squats down,

the hamstring must lengthen to allow hip flexion, but shorten to allow

knee flexion. The net result is little change in the length – that is,

little contraction – of the hamstrings. Little contraction translates to

little force production. The hamstrings function only as dynamic stabilizers, not prime movers, in any type of squat.

In short, no variation of squatting

adequately trains the hamstrings. Therefore it is unreasonable to choose

your squat variation with an aim to train the hamstrings. The squat

trains the quadriceps, adductors and gluteus, and the high bar and front

squats achieve this training more effectively than the low bar squat.

In King Squat Marty Gallagher makes the point in a more colorful fashion:

|

“The upright squatter uses an open stance, a "knees-out" ascent/descent and a full ROM. We force the quadriceps to do the all the work. We make squats a leg exercise, not some inferior hybrid/mongoloid technique that spreads the muscular effort between quads/hips/lower back and hamstrings.” |

Rather than futilely trying to make squats a good hamstring exercise,

one should do deadlifts, natural leg curls, or hip/back extensions on a

Roman chair to properly train the hamstrings.

High Bar Squat Develops More Mobility

Squatting deeper requires and develops greater knee and ankle mobility than more shallow squatting. This enables the trainee to train for greater lower body mobility at the same time as he/she trains for lower body strength. Therefore, since the high bar squat develops greater lower body mobility than the low bar squat while developing similar hip strength and similar or greater quadriceps strength, the high bar squat is a superior strength training squat.

Some advance the objection that many people can’t achieve a deep squat without excessive lumbar flexion, so they should adopt a partial squat such as the low bar squat. To this I answer:

If someone had such muscle stiffness as to be unable to do a full range of motion in the bench press, we would undertake training to improve the range of motion, not advise him to do a half bench press which will allow him to abuse his body with more weight on the bar than if he were trained to use a full range of motion. Just so, if someone lacks full range of motion in squatting, part of proper training should consist of restoring full range of motion either before or concurrent with learning the barbell squat.

Deep squatting is a normal resting position for humans outside civilization. I venture that of the many modern people who are unable to do deep squats, many have this limited range of motion not because of any anatomical limitation, but simply because they don’t regularly do deep squats. Sitting in chairs has made most people unfamiliar with this primal range of motion. I think many if not all people can achieve deep squats with training.

Before I addressed my hip mobility deficits, I strained my lower back multiple times when doing parallel squats which in fact are partial squats. Hence, I have concluded that skipping proper mobility training and doing restricted ROM squats just because it may seem difficult or time consuming to reclaim the ability to do full ROM squats is likely a dangerous practice.

Many novices to full squats will need to dedicate training time to improving hip and ankle mobility in order to achieve a deep position without undesirable lumbar flexion in the bottom. Those with limited mobility who want to pursue deep high bar squats should train squat mobility first, which is standard practice for individuals pursuing Olympic lifting wherein deep squats are virtually essential to success.

|

Simply spending some time every day in an unloaded or counter-loaded deep squat while activating the glutes will help restore your primal squatting ability. In my case, I have had to do more than this. I have gotten large benefits from squat training methods taught by Dr. Aaron Horschig, who offers excellent guidance and methods for restoring full range of motion to your squatting through his Squat University website, YouTube channel, and book The Squat Bible. |

In this video I show some of the results I have gotten from implementing some of Horschig's methods:

High Bar Squats Reduce Injury Risk

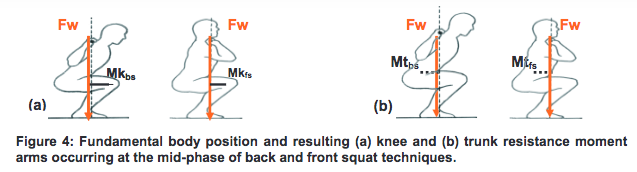

In comparing the back and front squats, Diggin et al explain that the greater the forward lean during squatting, the greater the trunk moment arm – Mt in the illustration (b) of Figure 4 below from Diggin et al. – and its torque.3 Thus, increasing forward lean increases the shear loading on the lumbar spine. The more upright the torso, the shorter the moment arm, and the less the shear loading of the lumbar spine. Shear loading on the lumbar spine would rank: low bar back squat > high bar back squat > front squat. Therefore, since the low bar back squat results in a greater forward

lean than the high bar squat, it also produces a greater shear load on

the lumbar spine, and consequently a greater risk of lumbar injury.

Source: Diggin et al.3

Similarly, Gullett et al. compared back and front squats and found “The front squat was as effective as the back squat in terms of overall muscle recruitment, with significantly less compressive [spinal] forces and extensor [hip] moments….front squats may be advantageous compared with back squats for individuals with knee problems such as meniscus tears, and for long-term joint health.”4

Like Diggin et al., Gullett et al. found that the more upright posture of front squats reduces forces that may increase injury risk compared to back squats.

Yavuz et al. compared front and back squats variations tracking the activity of the quadriceps hamstrings, gluteus, and erectors with EMG.5 The front squat produced greater quadriceps activation, while the back squat produced greater trunk lean, increasing the risk for lumbar injuries.

Hartmann et al. compared data on deep squats, half squats and quarter squats to assess whether the squats with less knee flexion were safer for the lower back and knees than deep squats.6 They found that the highest stresses on the knees occur with the joint at 90º, which is near the knee angle at the bottom of the low bar squat. Deeper full squatting actually reduces retropatellar compressive stresses. They found no evidence to suggest that deep squats increase risks for chondromalacia osteoarthritis, or osteochondritis, but concluded that performing half and quarter squat training with the comparatively supra-maximal loads they allow (compared to deep squats) will favor degenerative changes in both the knee and spinal joints in the long term.

This suggests that one may increase one’s risk of degenerative knee and lumbar spine changes if one chooses to perform low bar squats with their intrinsically limited knee ROM and usually greater barbell loads rather than full squats with the greater knee ROM which also limits total load. Using a high bar squat will provide equal or greater training effect for the hips and quadriceps with a lesser load on the spine.

It appears that the more upright high bar full squat reduces lumbar shear forces compared to the low bar back squat. The deeper squat, which most can achieve only with a high bar placement, appears to reduce risk of damage to the knees compared to a squat without full knee ROM. Since the high bar full squat provides equal or greater stimulation for quadricep and gluteus strength gains, but a likely lesser injury risk, compared to the low bar squat, I prefer the high bar squat.

Athletic Application

Of interest, Diggin et al also state: “The front squat also allows the performer to maintain a more upright posture throughout, a characteristic congruent with most sporting techniques (e.g.: sprinting). This would imply a greater level of specificity for this technique.”3

Similarly, the high bar squat’s more upright posture is more like the posture held in most athletic events than the low bar squat’s greater torso inclination.

Ease of loading and shoulder health

The low bar squat requires the performer to carry the bar below the scapular spine, whereas the high bar squat places the bar on the shelf formed by the trapezius. Unguided by any coach, most people will naturally choose to put the bar in the high bar position. One can support very high loads in the high bar position without any shoulder strain because the trapezius muscle provides both a natural shelf and a cushion on which the load may rest.

To hold the bar in place for the low bar squat, the performer must retract the shoulder blades and hold the humerus in the extremity of external rotation in order to put the posterior deltoid in a position to form a smaller shelf than the trapezius naturally provides. Consequently, the low bar squat position is more awkward and places the shoulders in a vulnerable position while not directly supporting, but stabilizing the heavy bar load. I speculate that this may increase the risk for shoulder rotator cuff injuries.

Why not just front squat?

As discussed above, the front squat probably provides a muscular strength training method equal in effectiveness to the high bar back squat, with possibly even less injury risk than the high bar back squat. So, why not just front squat?

First, loading the front squat is more difficult and uncomfortable than loading the back squat. One can more easily and comfortably load a heavy bar on the trapezius than the front shoulders and collarbone.

Second, related to this, maintaining the bar position in a front squat demands great upper back strength. Until one builds adequate strength in the upper back, one will limit the load one can use to train the naturally stronger hips and thighs.

For these reasons, for novice trainees, the high bar back squat is easier to learn and perform than the front squat.

Matt Foreman has written more about why one should not do only front squats in an article at Catalyst Athletics.

If you can do high bar full back squats with an upright posture, your increased injury risk will be small compared to the front squat, but you will be able to achieve the same full range of motion with significantly higher loads.

Over the long term, however, I would plan to include both high bar back squats and front squats in your program. One can start learning the front squat early in one's training, gradually building up the ability to rack and hold the bar. The front squat and the deadlift are complementary so once one has advanced to deadlifts with high loads, one may benefit from alternating days training the back squat with days training the front squat and deadlifts.

Summary

Compared to low bar squats, high bar back squats have these advantages:

- They train hip and quadricep strength over a greater range of motion.

- They place a similar training load on the hips and hamstrings but probably a greater load on quadriceps.

- They demand and produce greater knee and ankle mobility.

- They reduce lumbar shear loading and injury risk.

- They require a more upright posture more congruent with most athletics.

- They are more easily loaded with less stress upon and danger to the shoulders.

Therefore, unless your anatomy makes a low bar squat safer, or you need to put as much weight on the bar as possible to compete in powerlifting, I suggest that deep high bar squats (and front squats) have distinct advantages over low bar back squats for strength training and bodybuilding.

NOTES

- Contreras B, Vigotsky AD, Schoenfeld BJ, et al. A Comparison of Gluteus Maximus, Biceps Femoris, and Vastus Lateralis EMG Amplitude in the Parallel, Full, and Front Squat Variations in Resistance Trained Females. J Appl Biomechanics 2016;32(1):16-22.

- Bryanton MA, Kennedy MD, Carey JP, Chiu LZ. Effect of squat depth and barbell load on relative muscular effort in squatting. J Strength Cond Res 2012 Oct;26(10):2820-8.

- Diggin D, O’Regan C, Whelan N, et al. A biomechanical analysis of front versus back squat: injury implications. Portuguese Journal of Sport Sciences 2011;11(Suppl 2):643-646. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bc7c/48be4156f5f42b0add032b509c23c88681f6.pdf

- Gullett JC, Tillman MD, Gutierrez GM, Chow JW. A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. J Strength Cond Res. 2009 Jan;23(1):284-92. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31818546bb. PubMed PMID: 19002072. <https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/scmsAdmin/uploads/006/008/Gullet%20et%20al%202009%20-%20J%20Strength%20%26%20Conditioning%20Research.pdf>

- Yavuz HU, Erdağ D, Amca AM, Aritan S. Kinematic and EMG activities during front and back squat variations in maximum loads. J Sports Sci. 2015;33(10):1058-66. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.984240. Epub 2015 Jan 29. PubMed PMID: 25630691.

- Hartmann H, Wirth K, Klusemann M. Analysis of the Load on the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load. Sports Med 2013;43:993-1008. DOI 10.1007/s40279-013-0073-6

Recent Articles

-

Vegans Have The Highest Colorectal Cancer Risk? No

Mar 13, 26 05:37 PM

Do vegans have the highest colorectal cancer risk as recent Dunneram study claims? No! -

Ancient Roman Soldier Diet

Apr 14, 25 05:19 PM

A discussion of the ancient Roman soldier diet, its staple foods and nutritional value, and a vegan minimalist version. -

High Protein Chocolate Tofu Pudding

Jul 01, 24 12:41 PM

A delicious high protein chocolate tofu pudding. -

Vegan Macrobiotic Diet For Psoriasis

Sep 05, 23 06:36 PM

Vegan macrobiotic diet for psoriasis. My progress healing psoriasis with a vegan macrobiotic diet. -

How Every Disease Develops

Aug 04, 23 06:22 PM

How every disease develops over time, according to macrobiotic medicine. -

Why Do People Quit Being Vegan?

Jun 28, 23 08:04 PM

Why do people quit being vegan? How peer pressure and ego conspire against vegans. -

Powered By Plants

Mar 16, 23 08:01 PM

Powered By Plants is a book in which I have presented a lot of scientific evidence that humans are designed by Nature for a whole foods plant-based diet. -

Carnism Versus Libertarianism

Dec 30, 22 01:55 PM

Carnism Versus Libertarianism is an e-book demonstrating that carnism is in principle incompatible with libertarianism, voluntaryism, and anarchism.