Yoga: The Path To Freedom and God

What is yoga? Many people in western nations believe it is little more than a type of bodyweight exercise focused on stretching and achieving unusual postures called asana. I understand why. They have learned this from the proliferation of studios that focus on this physical training method.

When people call this physical training method "yoga" they are leaving off an important adjective, hatha. That method is properly called hatha yoga. The Sanskrit word hatha means "force, activity" to refer to the physical effort involved in this discipline.

Moreover, the Yoga Journal has published several articles (here, here, and here) revealing that what people today call hatha yoga did not originate in ancient India. Modern hatha yoga practice originated in the early 20th century when India was a British colony, and it is largely derived from 19th century European physical culture systems, including British gymnastics and a Scandinavian system called Primitive Gymnastics. A man named Krishnamacharya combined these European methods with some exercises he learned from Indian wrestlers and some old Indian physical culture texts and rebranded the mix as as hatha yoga. Thus the exercises themselves are not unique to yoga, but the approach to the exercises comes from the philosophy and science of yoga.

This physical training method is not the sum of yoga nor essential to the practice of yoga. Yoga is not a physical fitness method but a spiritual/religious philosophy, discipline/path, and goal.

In yoga philosophy it yoga has a threefold meaning. All of these meanings indicate that yoga is the path to freedom and spiritual strength.

Yoga Etymology

The word "yoga" is derived from the Sanskrit root yuj which means to bind, join, attach, to direct or concentrate upon, to use, to apply. The Sanskrit "yoga" and our English words "yoke," "join,"1 and "union" are derived from the same Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root *yeug-.

Thus anyone who practices yoga – known as a yogi – is seeking union, or to be yoked or joined to some being. What being? The Supreme Being, or Ultimate Reality, or True Nature, also known as GOD or TAO.

Patanjali's Yoga Sutras

Yoga is one of the six orthodox systems of ancient Indo-European philosophy. It was codified by Patanjali in his book Yoga-sutras.

|

Patanjali's Yoga-sutras – also known as yoga darsana – is the first and most systematic and authoritative presentation of both the theoretical and practical aspects of yoga. Patanjali also wrote textbooks on Sanskrit grammar and ayurveda––the science/knowledge (veda) of life (ayur)––the ancient Vedic system of health care and medicine. Of interest, Patanjali recorded important information about the castes and human races in ancient India. |

|

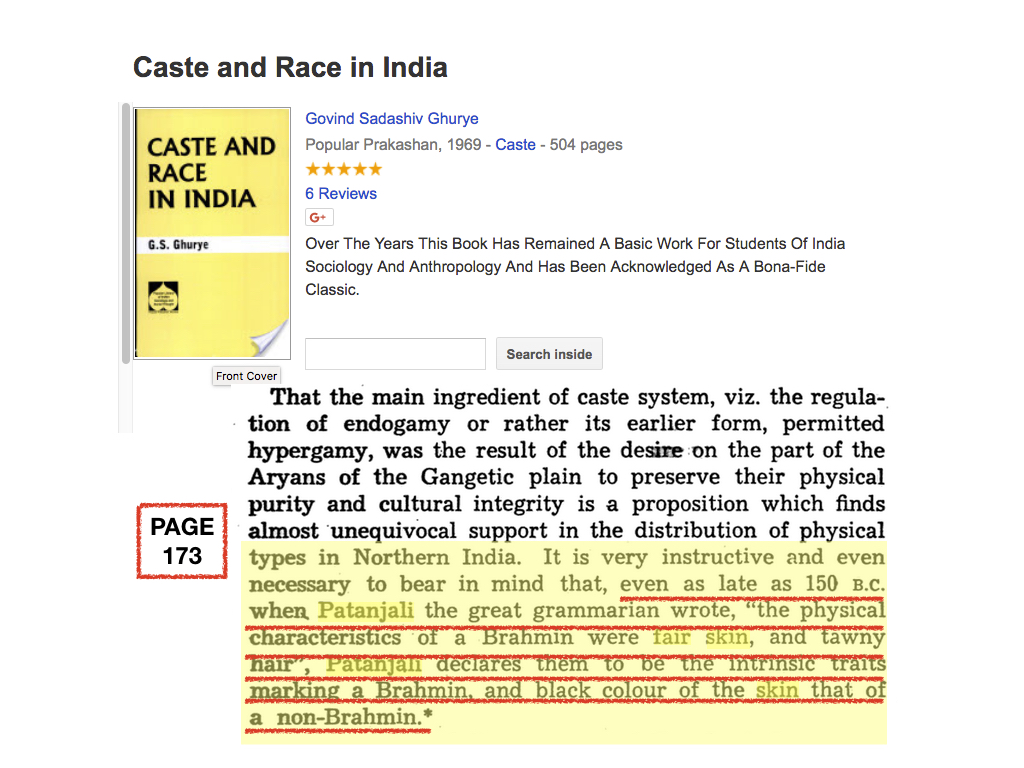

The Sanskrit word for caste, varna, actually means color, and is from the same PIE root as the English word "varnish". In the book Caste and Race in India Ghurye reports that about 150 B.C. Patanjali wrote that "the physical characteristics of a Brahmin were fair skin and tawny hair" whereas the non-Brahmins had dark skin color. |

|

In ancient Indian varna or caste system, the Brahmins were the scholars and spiritual leaders (priests), the other three castes being: the Kshatriyas or Rajanyas, the rulers, administrators and warriors (Sanskrit raja1 is cognate with the English royal); the Vaishyas, the artisans, tradesmen, and farmers; and the Shudras, the laborers.

Evidently the caste system was based on the observation that people of different human races had tendencies to different mental and physical constitutions and abilities. Since Patanjali was among the ancient scholar-priests in India, we can conclude that he had fair skin and tawny hair. In short, Patanjali was a Caucasian European.

But I digress. Back to yoga. In the Yoga-sutras, Patanjali lays out the theoretical basis and practice of yoga. He has little to say about asana, the physical postures that so many people call "yoga" these days. The book is divided into four parts (Sanskrit: padas) as follows:

- Samadhi pada (on contemplation)

- Sadhana pada (on practice)

- Vibhuti pada (on properties and powers)

- Kaivalya pada (on emancipation and freedom)

The first part is about quieting the mind (more about this below), not asana (postures). The second part, on practice, starts off with this statement:

|

"Burning zeal in practice, self-study and study of scriptures, and surrender to God are the acts of yoga." Yoga-sutras II.1 |

Patanjali then outlines the eight disciplines of yoga (astanga-yoga):

- Yama, or noble moral practice

- Niyama, or noble observances

- Asana, or seated posture

- Pranayama, or breath regulation

- Pratyahara, or sustained attention

- Dharana, concentration

- Dhyana, meditation

- Samadhi, absorption of consciousness in the self

The last 5 listed disciplines or limbs of yoga practice are all practices of regulating breathing and attention during meditation in order to achieve a direct experience of union with the Supreme One, which you may call God. They are beyond the scope of this article except to note that they are not types of physical postures as taught at modern 'yoga' studios; and that Patanjali repeatedly warns his readers that it is dangerous to engage in those advanced meditation practices without laying a proper foundation with practice of moral conduct and noble observances.

The yogic moral law includes non-violence (not initiating force against others), honesty (telling truth not lies), non-stealing (not taking what belongs to others), sexual continence (no sex or even lust outside marriage), and non-greed/non-covetousness (possession of only what one needs, not coveting the goods owned by others). Patanjali says all people should obey this code at all times and in all places (Part II.31).

This is yoga practice because through noble conduct one strived for union with God's Will expressed as the Universal Natural Law "do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself." Practicing the moral discipline requires the yogi to forgo his egotistical desires to take advantage of others by taking life, liberty or property from them, and to submit himself to God (Truth, Tao) and His Will (Moral Law). B.K.S. Iyengar, highly accomplished yogi and author of Light on Yoga and one of my favorite commentaries on the Yoga-sutras of Patanjali has written that genuine yoga is "the true union of our will with the will of God."

Thus there is no yoga without morality, and anyone who strives to do God's will via moral righteousness practices yoga. Conversely, those who deliberately break God's Moral Law do not actually practice yoga, no matter how much time they spend doing physical exercises at the "yoga" studio.

The niyamas or noble observances are: cleanliness, contentment, enthusiasm, study leading to self-knowledge, and surrender of oneself to God.

Regarding surrender to God (bhakti-yoga), Patanjali says:

|

"Surrender to God brings perfection in samadhi." II.45 |

Samadhi (absorption) refers to a state of profound meditation and spiritual integration that develops in six stages, ultimately leading to direct experience of yoga – union – with the One Supreme Being. Thus he asserts that surrender to God (and His Will) is the essence of yoga.

Indeed, in the Bhagavad Gita (Song of God), the Blessed Lord (incarnated as Krishna) says the same to the warrior Arjuna:

|

"Those who, fixing their mind on Me, worship [obey] Me with complete discipline and with supreme faith, them I consider to be the most learned in yoga." Bhagavad Gita XII.2 |

Jesus the Christ similarly taught that one must surrender to God's will and adhere to the spirit of His commandments in order to qualify to enter the kingdom of heaven, which is not of this world or realm (John 8:23, 18:36) but within you (Luke 17:21).

|

"Not everyone who says to Me, 'Lord, Lord,' will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only he who does the will of My Father in heaven." Matthew 7:21 | |

|

"Why do you call me Me 'Lord, Lord' and not do the things which I command?" Luke 6:46 | |

|

"Do not presume that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish, but to fulfill. For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke of a letter shall pass from the Law, until all is done! Therefore, whoever nullifies one of the least of these commandments, and teaches others to do the same, shall be called least in the kingdom of heaven; but whoever keeps and teaches them, he shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven. For I say to you that unless your righteousness far surpasses that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven." Matthew 5:17-20. |

Patanjali devotes nine sutras to the practice of morality and six to the practice of noble observances, compared to only two discussing asana/posture. Here let me note that the Sanskrit word asana actually means "sitting down" (from the Sanskrit root as = "to sit down"), a sitting posture, a meditation seat. Thus originally asana refers only to seated posture conducive to still meditation and concentration, and not the various standing, twisting, hand balancing, and other non-seated poses and movements that practitioners of hatha yoga practice and call asana. Strictly speaking, from a physical standpoint alone, if you aren't in a seated posture, you aren't doing asana.

The two verses on asana / sitting posture follow:

|

"Asana is perfect firmness of body, steadiness of intelligence and benevolence of spirit." II.46 | ||

|

"Perfection in asana is reached only when the effort to perform it becomes effortless and the infinite being within is reached." II.47 |

Thus Patanjali did not suggest practice of any set of specific physical postures such as presented by hatha yoga advocates. In II.46, Patanjali says that by posture/asana, he means firmness of body, steadiness of intelligence and benevolence of spirit. He does not specify any particular physical discipline for achieving firmness of body. Nor does he list or describe any specific posture(s). Any physical discipline that leads to firmness of body – including proper strength training – can therefore contribute to attaining the noble asana described by Patanjali.

Let me clarify. Since Patanjali's description of posture includes steadiness of intelligence and benevolence of spirit, he appears to be using posture (asana) to refer not only to sitting posture conducive to meditation, but also to one's overall physical-mental-spiritual pose, in a word, one's dis-POSE-ition. A yogi should always cultivate a posture of physical firmness, mental steadiness, and benevolent spirit, no matter what specific physical posture or action one happens to be in at any time of day (lying, sitting, standing, squatting, twisting or bending, etc.). In another word, a yogi should keep himself benevolently alert at attention, like a warrior on watch to protect his people. This especially applies when practicing meditation, as indeed there are principles of posture one must apply to remain alert (stable base, erect spine, etc.) during extended meditation practice.

Stable Postures for Extended Meditation

|

|

|

|

|

Seiza |

Quarter Lotus |

Half Lotus |

Full Lotus |

Thus, yoga is a noble path to union with Supreme Being (God, Tao, Ultimate Reality) by route of subduing the ego and surrendering to God's Will (Moral Law). Thus any one who practices morality, nobility, and surrender to Moral Law in action (karma-yoga) and meditation practices yoga. Any stable seated posture conducive to meditation and concentration is a yoga-asana.

Yoga = Silence of Mind

|

The Kathopanishad describes yoga thus: "When the senses are stilled, when the mind is at rest, when the intellect wavers not–then, say the wise, is reached the highest stage. This steady control of the senses and mind has been defined as yoga. He who attains it is free from delusion." |

In the second aphorism of the first chapter of the Yoga-sutras, Patanjali describes yoga as "chitta vrtti nirodha" which translates as subsidence or quieting of the modifications of the mind.

Spend a few moments in silence, paying attention to your mind. Observe its restlessness. The restlessness and recalcitrance of the mind indicates it is a powerhouse. Left to its own devices its energy is wasted. It is like a wild horse, which if tamed and harnessed properly could do positive work rather than wreaking havoc.

Thus yoga is the eightfold method by which the restless mind is tamed and trained to the Supreme Being and Ultimate Truth rather than distracted by temporary phenomena.

Through proper meditation and concentration, the yogi develops a one-pointed mind and this leads to yoga or union with the Lord:

|

"May we harness body and mind to see the Lord of life, who dwells in every one. "May we ever with one-pointed mind strive for blissful union with the Lord. "May we train our senses to serve the Lord through the practice of meditation." Shvetashvatara Upanishad II.1-3 |

A dedicated yoga meditation practice will transform the yogi, freeing him from disease and cravings.

|

"Health, a light body, freedom from cravings, a glowing skin, sonorous voice, fragrance of body: these signs indicate progress in the practice of meditation." Shvetashvatara Upanishad II.12-13 |

Yoga = Liberation Path

All schools of so-called Indian philosophy, including yoga, assert that there are four great aims of the good life: nobility or virtue (dharma), adequate wealth (artha), pleasure (kama), and freedom (moksa). The Sanskrit word for freedom, moksa, derives from the root muk, meaning "to free," "to emancipate," "to release."

Practice of the eight limbs (ashtanga) of yoga leads one to freedom (Sanskrit: moksa) or liberation (kaivalya):

|

"Kaivalya, liberation, comes when the yogi has fulfilled the purusarthas, the fourfold aims of life, and has transcended the gunas. Aims and gunas return to their source, and consciousness is established in its own natural purity." Yoga-sutras IV:34 |

Practicing moral conduct (yamas) frees us from the ego and slavery to the addictions of the five senses. Moral conduct also frees us from tyranny and gives us a free society. A nation without morality is immersed in crime, each man infringing upon and taking life, liberty or property from his neighbors. In such chaos the people will live in fear and beg for a tyrant to 'lay down the law' to create order. You either govern yourself with noble moral conduct, or you will be governed by others infringing upon your rights and sovereignty.

Practicing the noble observances develops further self-knowledge and self-mastery, which enables one the freedom to accomplish whatever goals one might have.

Practicing cleanliness and physical training methods frees the body from disease.

Practicing yoga meditation frees the mind from disturbance, anxiety, and cravings that would lead to immoral conduct and cloud one's vision.

Ultimately, practicing yoga frees the mind from the ignorance and delusion that creates all suffering:

|

"But, one might ask, freedom from what? The answer to this question is the quintessence of Indian wisdom. Let us first point out that the very fact that Indian philosophies regard moksa as the ultimate goal of life points to the extraordinary significance they attach to the essentially spiritual nature of man. According to all Indian schools of philosophy, man's state of suffering and unfreedom is not due to any original sin but to original ignorance (avidya) of his true being and nature. Thus the Upanishads teach that man in his true being is Atman (Brahman, ultimate reality), which is infinite, eternal, and immortal. | |

|

"But in his ignorance, man identifies himself with finite and perishable things, such as his body, mind, ego, and thereby develops attachments to them and suffers sorrow and misery when he loses them, as he inevitably does. It is only by attaining the knowledge that in his true being he is indeed ultimate reality that man can conquer ignorance and bondage and become free...every school of Indian philosophy recognizes Yoga in some form or other as the physical-mental discipline necessary for the attainment of moksa."2 ––Ramakrishna Puligandla |

Many people think freedom is the ability to do whatever one wants. Well, yes, we all have such "freedom" but there is a catch: on this plane, all actions have consequences. You pay to play, and reap what you sow. This is the doctrine of karma. If you play this game foolishly and in ignorance, you will reap only disease, pain, sorrow, and misery.

Yoga outlines the way to play the game wisely. Through the practice of yoga, you will sow good seed and consequently reap good fruits. Moreover, through yoga you can ultimately transcend this mundane world and directly know God, the True Nature and Highest Good of All.

Notes

1. Although in modern English we pronounce the letter "j" like a soft "g", historically the "j" was practically interchangeable with and pronounced like a "y" (I am sure you can see the similarity between the two letters). This is carried on in German wherein for example the name "Johan" is pronounced "Yohan" whereas the English equivalent is John.

2. Ramakrishna Puligandla, Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy (Abingdon Press, 1975), p. 22-23.

Recent Articles

-

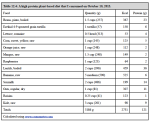

Ancient Roman Soldier Diet

Apr 14, 25 05:19 PM

A discussion of the ancient Roman soldier diet, its staple foods and nutritional value, and a vegan minimalist version. -

High Protein Chocolate Tofu Pudding

Jul 01, 24 12:41 PM

A delicious high protein chocolate tofu pudding. -

Vegan Macrobiotic Diet For Psoriasis

Sep 05, 23 06:36 PM

Vegan macrobiotic diet for psoriasis. My progress healing psoriasis with a vegan macrobiotic diet. -

How Every Disease Develops

Aug 04, 23 06:22 PM

How every disease develops over time, according to macrobiotic medicine. -

Why Do People Quit Being Vegan?

Jun 28, 23 08:04 PM

Why do people quit being vegan? How peer pressure and ego conspire against vegans. -

Powered By Plants

Mar 16, 23 08:01 PM

Powered By Plants is a book in which I have presented a lot of scientific evidence that humans are designed by Nature for a whole foods plant-based diet. -

Carnism Versus Libertarianism

Dec 30, 22 01:55 PM

Carnism Versus Libertarianism is an e-book demonstrating that carnism is in principle incompatible with libertarianism, voluntaryism, and anarchism. -

The Most Dangerous Superstition Book Review

Nov 15, 22 08:46 PM

Review of the book The Most Dangerous Superstition by Larken Rose.